Maybe the use of the word “travesty” is quite possibly a bit of hyperbole; however, it is the word that comes to mind when one considers the usually narrow exposure most students and economists have with other economic systems. In most universities on this side of the globe, the textbooks “educate” most of us to extol and place on a pedestal one predominant form of the market economy and its inherent assumptions. Those assumptions become a form of cantillation, whereby, we begin to intone the ideals of the “rational consumer,” the “profit-seeking” entrepreneur, and the supposed allocative efficiency of the price mechanism in the market is apotheosized.

While one cannot completely disregard the utility of some of the foundational assumptions when placed within their appropriate contexts, as the veils of ceteris paribus continue to lift, one component that is increasingly gaining traction within the Comparative Economics literature is the role played by the national cultural values. Said differently, at the heart of the traditional assumptions, there is the inherent and undergirding philosophy that economic agents are largely the same in terms of their driving force and incentives. But as we learn more via research, is that premise entirely true, especially when one recalls that every group of people carry with them their own set of cultural values that, in turn, define goals?

In 2020, the research duo, Thomas Bradley and Paul Eberle, published their paper that touches on this salient point (Bradley and Eberle 2020). Using the seminal work of Geert Hofstede (1980)’s Cultural Dimension Index (“CDI”), they examined the nexus between countries’ disparate economic systems and their CDI scores. The exercise confirmed what most social scientists may have already suspected: That there is an inextricable link between culture and the way people of a particular community or society go about solving economic problems.

The CDI and Systems

To help others appreciate Bradley and Eberle (2020)’s findings, we must digress a bit towards a brief explanation of the CDI’s domains. Since Hofstede (1980) first introduced the CDI, the index has advanced somewhat to now incorporate six dimensions: Power Distance, Individualism, Masculinity, Uncertainty Avoidance, Long-term Orientation, and Indulgence. The six dimensions are scored from zero to 100.

High Power Distance (PD) speaks to a cultural dynamic that accepts power differences, with citizens of the country in question tending to show a great deal of respect for hierarchy and for those in authority and of rank. Countries like Saudi Arabia and Guatemala carry high PD scores (both at 95). Conversely, the United States and the United Kingdom have much lower PD scores at 40 and 35, respectively. The lower scores for the United States and the United Kingdom are not surprising considering their political structure and institutions.

A high level of Individualism (IND) speaks to the fact that such a society places a greater premium on individual goals and responsibilities. Inversely, low individualism is synonymous with a collectivist society where more weight is placed on the well-being of the collective or society as a whole. As Hofstede defines this dimension, IND can be defined as “a preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals are expected to take care of themselves and their immediate families. Its opposite, Collectivism, represents a preference for a tightly-knit framework in society in which individuals can expect their relatives or members of a particular in-group to look after them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty. A society’s position in this dimension is reflected in whether people’s self-image is defined in terms of ‘I’ or ‘we.’” With that definition in hand, it should be of little surprise, then, to find that Venezuela’s IND statistic is found at the lower end at 12, while the United States’ IND has been set at 91.

Among other things, a society high in what the CDI has labeled as “Masculinity” (MAS) tends to place greater emphasis on competitiveness and “material rewards for success.” A lower score on MAS is said to speak to a preference for “cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak and quality of life. Society at large is more consensus-oriented.” Nordic countries like Sweden and Norway—which have strong welfare systems—are found to have very low MAS values of five (5) and eight (8), respectively. For the United States, the value here is 62, and for both China and the United Kingdom the score is 66 on the CDI. For the latter group (i.e. USA, China, and UK), the CDI signals their cultural preferences for more competition and material rewards, and less emphasis on consensus-building and “caring for the weak” as one may find in Sweden and Norway.

Uncertainty Avoidance (UA) has to do with the society’s risk appetite. More precisely, as Hofstede explains it, it has to do with the “degree to which the members of a society feel comfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity.” Consequently, high levels of UA may manifest itself as a society that prefers rigid codes and conservative behavior that is not very open to “unorthodox behavior or ideas.” Conversely, the lower rankers on UA are expected to have a higher tolerance for risk-taking—a key component of entrepreneurial activities and innovation.

Finally, Long-term Orientation (LTO) speaks to how societies approach preparing for the future. Higher rankers would tend to display an attitude of delaying immediate-term gratification in favor of long-term goals, while the lower scores on the LTO indicate a more short-term orientation that may manifest as a preference for immediate results and instant gratification. New Zealand is among the countries with fairly low (or short-term) LTO values as it scores at 33. On the other hand, China was found to display higher levels of LTO (87).

Return to Culture and Economic Systems

Having briefly reviewed the CDI, we are now able to return to the economic system’s conversation. Bradley and Eberle (2020)—using the mean scores among country groups—were able to demonstrate that countries with disparate systems resonated with their cultural values as measured by Hofstede (1980).

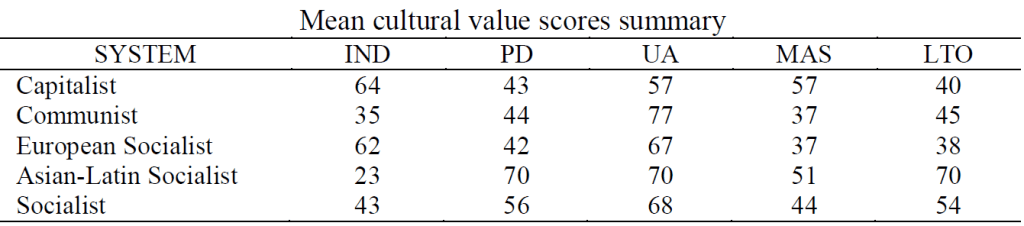

Grouping systems into five groups—a debatable approach considering the emergence of the tenets of the Varieties and Diversity of Capitalism schools of thought (see Hall and Soskice 2001, and Amable 2003)—Bradley and Eberle was able to show that each system had a unique relationship with the cultural dimensions. Capitalism, on average, displayed higher levels of Individualism (64), relatively low-to-moderate Power Distance (43), moderate Uncertainty Avoidance and Masculinity (57), and relatively low Long-term Orientation.

Communist countries, for their part, were found—unsurprisingly so—to display, on average, lower Individualism (35), low-to-moderate power distance (44), high levels of Uncertainty Avoidance, lower Masculinity (37), and low-to-moderate LTO. The lower MAS score for communist countries is to be expected considering that low MAS signifies societies that place greater emphasis on improving the “quality of life” of its members with relatively less focus on material achievements.

An intriguing observation is that of the European Socialist economies that for the most part mirror “Capitalist” systems, save for the lower Masculinity value, which, again, prioritizes the welfare of the society’s members over material gains and competition.

Bradley and Eberle (2020) also classify certain countries’ systems into an Asian-Latin Socialist model. While both the European and the Asian-Latin wear the term “Socialist,” their expressions and approaches to achieving the goals differ significantly. On average, the Asian-Latin societies were found to have significantly lower values for Individualism (23) relative to the European model. Additionally, the manifestly higher levels of Power Distance (70), and Long-term Orientation (70).

The Institutional Channels

The shaping of a society’s economic system in alignment with its national cultural values (as measured in this instance via the CDI) is a testament to how culture, social norms, beliefs, and factor endowments influence the jurisdiction’s institutions.

In the Nordic countries, for example, we have already seen where their lower MAS score speaks to a society that prioritizes the “quality of life” of its members. As a result, among other interrelated factors, economic policy and institutions evolved in such a way to support a more welfare-oriented system. In Sweden, for instance, this welfare is pronounced in its publicly funded healthcare, education, and a host of social protection programs.

While Capitalist systems such as that found in the United States do have their fair share of social programs, the emphasis is notably different, especially when one tunes in to the ongoing policy debates in the USA over social spending.

Additionally, these formal and informal institutions are often times inter-generational as they are usually self-reinforcing. For this reason, the literature in this area of research holds the view that while there may be some cultural drift over time, the relative positions across varying societies are likely to remain unchanged.

A Place for a New Paradigm

Undoubtedly, the conversations on comparative economic systems are extensive, but the point being made here is that, as the world learns more about what informs the “design” of disparate economic systems, we should be prepared to simultaneously modify how we counsel economies. There is, therefore, a need for the crystallizing of a new paradigm as it pertains to economic policy advice, especially when this advice comes from external sources.

Ultimately, there is value in first comprehending the cultural dynamics of society before adopting economic policy positions. Practically speaking, to do anything less is to virtually doom the execution of incompatible policies to immediate or eventual failure. Even within the public-policy analysis domain—which is where Res Publica360 is written from—this latter point should resonate with the “value acceptability” consideration that is nestled within John Kingdon (1984)’s larger multiple streams model for agenda-setting.

The fact is that at the heart of national culture one will find societal “goals.” These goals can be quality-of-life specific á la the Nordic countries, or more focused on individualized material success. Similarly, these aims could emphasize long-term objectives such as environmental protection and sustainable development. Regardless of the goals, the point must be made that the standard assumptions—for decades—have unfortunately ignored these salient considerations under the themes of ceteris paribus, a “tool” utilized to simplify economic concepts but was never intended to lead the way. The inescapable truth is that all things are not equal, and this includes economic systems that are as unique as the societies’ cultures that build them.