“There are also signals that the lack of fiscal discipline could be linked to political cycles. … In fact, the three years when the government’s budget balance reached its low-point before reverting towards balance (1984, 1993, and 2003) were election years”—Hausman and Klinger (2007, p. 13).

“According to the reported results, there is a POSITIVE RELATIONSHIP between elections and public debt accumulation. Given the positive effect, our evidence suggests that, relative to pre-election period, there is about 36% probability that presidential election periods are characterized by higher debt”–(Bayale et. al, 2020, p. 39).

The first opening quote above is from the “Growth Diagnostic of Belize” that had applied the Growth Diagnostic Framework and methodology to answering the age-old question: “Why is investment in Belize low?” In using the said framework—which has since been applied at least three times to the Belizean economy—researchers Ricardo Hausman and Bailey Klinger highlighted the fact that government’s fiscal balances tend to deteriorate just prior to a General Election.

The second is from a study entitled “More elections, more burden? On the relationship between elections and public debt in Africa.” In this one, Bayale et. al (2020) use data for fifty-one (51) African countries to empirically demonstrate the positive correlation between public-sector debt and Presidential Elections.

The intriguing thing about these studies is that while written roughly 13 years apart and about significantly different countries, the consensus remains: Without proper controls and institutions, prudent fiscal practices tend to go through the window around election time.

Belize’s Primary Balance & General Election Cycles

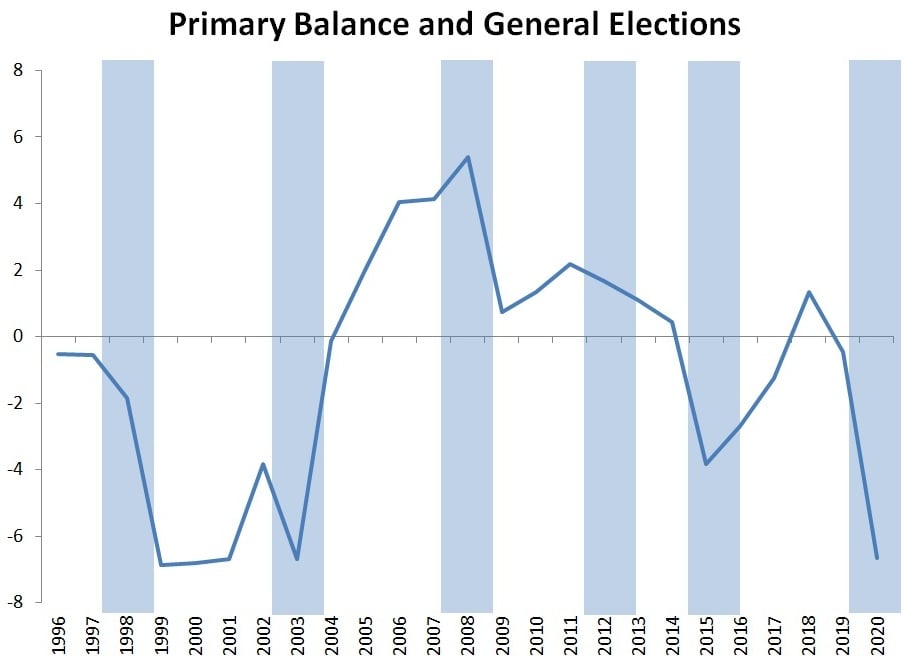

Using IMF’s data (April 2021), it is possible for someone to crosscheck this for themselves. For Belize, this trend is likewise observable, as is shown in the accompanying graph.

Belize has had six General Elections between 1998 and 2020 (1998, 2003, 2008, 2012, 2015, and 2020). Excluding 2020 for obvious ‘COVIDIOUS’ reasons, it is worth noting that all election years (except 2008) saw the primary deficit (PD) widen relative to the immediately preceding year.

Let’s be a little more specific. The primary balance—the difference between government’s revenues and non-interest expenditures—was -0.55% of GDP in 1997, before sinking further to -1.85% in 1998.

In 2002, the deficit was -3.82% before deteriorating further to -6.7% in election year 2003. In 2012, there was a primary surplus of 1.66% (down from 2.18% in 2011). The deficit was 0.43% in 2014 before slipping back into negative territory in 2015, when it widened to -3.84% of GDP.

Now, yes, there was a 2020 General Election, but let’s be honest: Nothing was normal about that year.

These deficits, of course, matter because they are generally financed via borrowing. Furthermore, in jurisdictions with weak oversight mechanisms and institutions, it is not uncommon for campaign ‘financier”’ to become the ultimate driver for inefficient economic policies.

Debt and Campaign Finance Laws

With the foregoing in mind, it is, therefore, possible for one to say that the lack of controls as to the type of spending that occurs during election season does come at a “cost” to the public—after all public debt is ultimately paid by the taxpaying public.

So, what can we do to address this? Well let us start here: With Campaign Finance Legislation (CFL). There are many models and real-world examples to choose from, but we do not have to look too far, because just last year the, then, Senate President Darrell Bradley had presented a draft CFL. Section 15 of that proposed law read as follows:

“(1) No moneys from the Consolidated Fund, or moneys voted on or appropriated by the National Assembly of Belize, or moneys otherwise belonging to the government of Belize or for which the government of Belize is entitled to, shall be used, either DIRECTLY or INDIRECTLY, to finance any election campaign or to influence the outcome of any election.

“No government resource or state-owned property…government employees, shall be used by a political party or candidate, either DIRECTLY or INDIRECTLY, to assist in or support any election campaign or to influence the outcome of any election.”

The reality that inspires the need for such language to appear in any draft CFL is known to most Belizeans. The fact is that it’s so common that someone could often hear the quip: “What road di get fix; elections must be close!” The comment, often designed to be facetious, echoes a very real sentiment: To sway voters, state resources tend to kick into full gear in the lead up to Election Day. At the same time, the opposition politicians—unable to employ such state-sponsored influence— would be busy trying to outspend their incumbent rival, an act that may lead them to questionable campaign financiers.

Therefore, the logic in section 15 of Bradley’s text is conspicuous; however, also important is the overall concept of a spending limit for political campaigns. Section 23 of the draft CFL addressed this matter as follows: “No political party shall spend in excess of $2,000,000.00 in any one election campaign period.”

Now, let’s be clear here. That was a draft CFL; therefore, even the precise expenditure limit should be open to debate. Nevertheless, the focus here is on the principle of capping election spending, in a context that also demands increased political-party transparency for both the contender and the incumbent.

Fundamentally, the goal—as far as this discussion is concerned—is to disrupt the conditions that gives rise to the type of election-deficit trend observed, and to completely dislodge Belize’s public finances from the political cycle.

And there will be the “Average Joe and Jane” that asks: “How does this affect my life?” Two general answers exist: Firstly, it has been empirically proven that high public debt drags down economic growth, which ultimately could translate into things such as lack of jobs in the private sector and lower tax revenues to fund social assistance programs (unemployment relief, wage subsidies, etcetera). Secondly, high public debt keeps the country “vulnerable” to external shocks like COVID-19. This is part of the reason the Government of Belize has been unable to have a “strong” fiscal stimulus response during the ongoing crisis.