Since Independence there have been eight amendments to the Belize Constitution. In 1985, there was the Belize Constitution (First Amendment) Act (No. 14 of 1985), which, inter alia, addressed certain nationality matters, including the issue of Dual Nationality as found at Section 27 of the Constitution.

Three years later, the records show that there was the Second Amendment Act (No. 26 of 1988), which, again among other things, gave us the Elections and Boundaries Commission (Section 88). The third amendment came thirteen years later in 2001, with the Belize Constitution (Third Amendment) Act, 2001 (No. 2 of 2001). The third amendment was fairly extensive and impacted the operations of the Public Service Commission (PSU), looked at the Security Service Commission, touched on the tenure of office of Justices of the Supreme Court, and even made changes relevant to the Cabinet.

In the same year, there was also the Fourth Amendment (No. 39 of 2001), which looked at the Belize Advisory Council (BAC), and, inter alia, amended areas relevant for the functions of the Senate. Four years later there was the Fifth Amendment (No. 23 of 2005) that looked at the Magistracy (Section 93A) and “Remuneration for certain officers” (section 118).

The Sixth Amendment would follow three years later (No. 13 of 2008) and it made changes to several areas of the Constitution, including section 17 which provides “protections from deprivation of property”. It would take another two years before the Seventh (No. 4 of 2010) arrived to make changes that included those relevant for the appointment of Ministers of Government (section 40), especially as it pertains to the appointment of the Attorney General.

And then, of course, there’s the infamous Belize Constitution (Eight Amendment) Act, 2011, which was predominantly designed for the Government to maintain control of the Public Utilities. Its purpose is probably best articulated in the amendment made to section 144 of the Constitution which now reads: “From the commencement of 25th October, 2011, of the Belize Constitution (Eight Amendment) Act, 2011, the Government shall have and maintain at all times majority ownership and control of the public utility provider.”

There is always room to debate the changes made over the years, especially in terms of the Eight Amendment, which was soaked in controversy. However, it cannot be ignored that those eight amendments occurred over the span of almost three decades—from 1985 to 2011.

The People’s “CONTRACT”

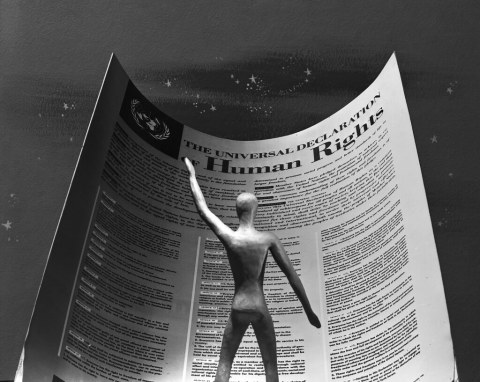

The Constitution could succinctly be defined as the codification of the Will of the People. This is part of the reason why the Constitution of Belize’s preamble opens with the phrase: “WHEREAS the people of Belize”. More than anything, this is the People’s document, which provides, at least, three basic functions: (a) to first and foremost provide protections for citizens’ individual liberties and rights, (b) secondly, to give life to “trias politica” (Separation of Powers) principles, and (c) closely related to trias politica, establishes a government that should be “of the people, for the people, by the people”.

One could, therefore, think of the Constitution as the “supreme contract” between the People of Belize (the true rulers in a democracy) and the Government of Belize (GoB).

Now, for any commonplace contract, it is common knowledge that terms in a contract cannot be unilaterally altered. The Parties to the Contract are required to communicate—in one form or the other—whether they agree to any alterations. Keeping, then, with this analogy, one would be right in asking the question: How do the People of Belize communicate our desire for (a) any change to the People-to-Government Contract, and (b) upon deciding that there is indeed a desire for some change, how do we go about deciding on exactly what those changes ought to be?

The “Curse” of the Supermajority

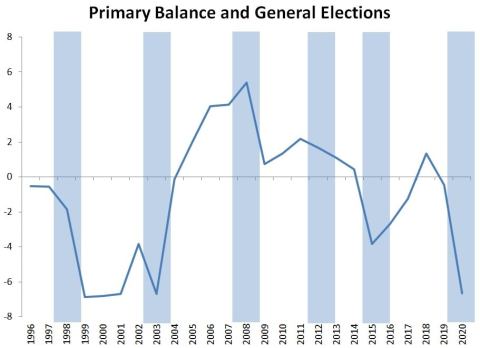

There is space for quite a robust debate as one tries to answer that question; however, the post-independence trend seem to suggest that at least one party to the “supreme contract” believes that the answer lies in the results at the polls.

If one would review the First through Eight amendments, a conspicuous pattern emerges: That is, changes to the Constitution are made whenever one political party wins a “supermajority”. In 1985 and 1988, the United Democratic Party (UDP) controlled 21 out of the then 28 seats in Parliament, thereby, giving it well above the two-third votes required for Constitutional amendments.

The “silence” between 1988 and 2001 could be largely attributable to the fact that no such supermajority re-emerged until 1998, when the People’s United Party (PUP) won 26 of the then 29 Parliamentary seats. It took about two years, but eventually the PUP started their own tinkering with the Constitution, giving us the Third and Fourth Constitutional amendments in 2001.

Having maintained dominance in House after the 2003 General Election, with the voters giving the PUP 22 seats in the House of Representatives (“The House”), it took the Musa Administration about two years before they instituted the Fifth Amendment in 2005.

Then, of course, most would recall the results of the 2008 General Elections, wherein the UDP was returned to office with a supermajority (25 to 6 seats). This era gave us the remaining three changes to the People’s contract (i.e. the sixth to the eight amendments). The subsequent General Elections didn’t yield a supermajority; therefore, for roughly ten years there were no changes to the Belize Constitution.

Last November, however, the people, once again, returned a supermajority to The House, giving the PUP 26 out of the 31 seats. And while the Musa Administration seemed to have applied a two-year “buffer” before pulling the Section 69-trigger, that does not seem to be the case with the present administration, which as proposed three in about eight months.

A Mandate?

Several things are observable from this trend. First, the fact that changes only seem to occur when one party enjoys a supermajority in the House is indicative of an inability or unwillingness of politicians to obtain bi-partisan support for the changes. The second observation is that political parties seem to take the view that the size of their victory at the polls directly signals the People’s “permission” or “support” for Constitutional Amendments.

The second point, however, is the most salient. The Belizean people will have to “speak up” (as the saying goes) as to whether or not a “big win” at the polls should be automatically interpreted as carte blanche license. The fundamental principle governing the “supermajority” requirement is that democracies should carefully deliberate Constitutional alterations; they ought not to be done whimsical or for political expediency.

Tenth and Eleventh Amendments

To that end, it cannot be lost the Belizean People that in just under eight months, the current government is in the process of proposing three amendments, with the tenth and the eleventh amendments being the most troubling of the bunch.

In the case of the Belize Constitution (Tenth Amendment) Bill, 2021, the government is seeking to change the tenure rules for members of four Constitutional enshrined institutions: The Belize Advisory Council, the Elections and Boundaries Commission, the Public Services Commission, and the Security Services Commission. Essentially, if passed, the proposed change would make each of these important institutions subject to the political cycle.

The Eleventh Amendment—at least based on what has been circulated in the media thus far—seeks to add new disqualifications for persons vying to become members of Parliament. If passed, this amendment would cause the Supreme Law to read as follows:

“No person shall be qualified to be elected as a member of the House of Representatives who … (da) has served a sentence of imprisonment for more than twelve months, imposed by a court in or outside of Belize; or (db) is under a sentence of imprisonment, or has served a sentence of imprisonment, imposed by a court in or outside of Belize, for an offence in relation to corruption or abuse of public office.” Clearly, there is some value in the latter provision, so as to ensure that proven corrupted officials cannot hold the reins of power. However, the citizenry must carefully weigh whether the former section (da) reflects the will of the Belizean People. The same question ought to be asked of the Tenth Amendment.